Considered one of the seminal French texts on film and education, The Cinema Hypothesis: Teaching Cinema in the Classroom and Beyond by Alain Bergala is newly available in an English translation, published by SYNEMA Society for Film and Media, Austrian Film Museum. Here’s a Google translation of the book description:

“The former chief editor of the “Cahiers du cinéma” deals with the potentials, possibilities and problems of film in the school context without sacrificing his own deep passion for the cinema and his lifelong preoccupation with it.”

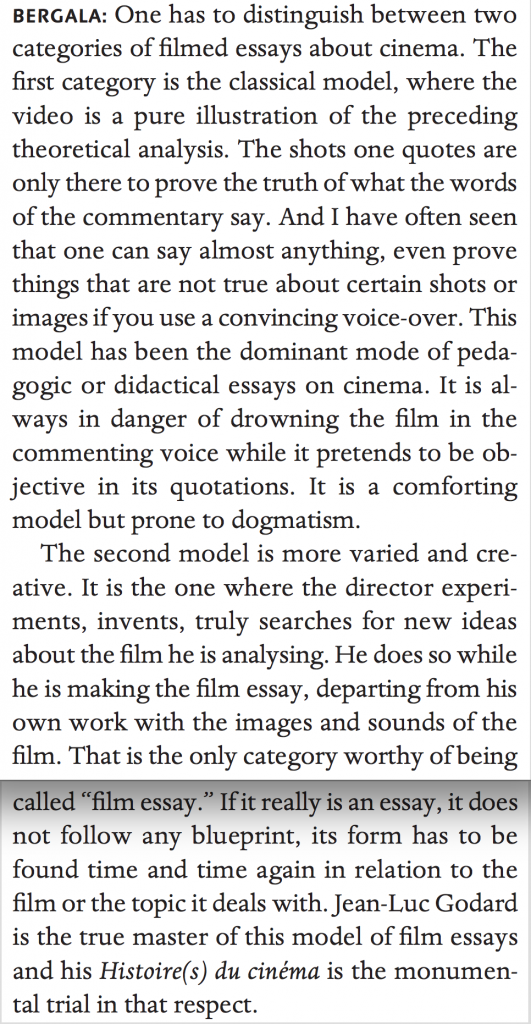

In addition to the translation of the original book, this publication includes an interview with Bergala conducted by Alejandro Bachmann of the Austrian Film Museum. In the course of the conversation Bergala comments on the current mode of videographic film studies (video essays) and divides them into two groups:

Further along in the book description, more words that resonate with me:

“Film has to resist the institutions on which it is taught and the concept of education that prevails in it. The attempt to bring young people into contact with the cinema must produce a friction, a feeling of the “other”; an experience that can change your life.

Taking these two passages together surfaces a crucial paradox in the relationship between moving image art and pedagogy, one akin to that which exists between creative freedom and systemic order. To teach someone to think and act freely, is this not an oxymoron? There are video essays that offer a sense of freedom or liberation from the norm but effectively offer a new norm in its place for viewers to subscribe to without a second thought. In these cases, the productive friction Bergala endorses gives way to a new encasement.

I forget my first exposure to Bergala, it was either during one of my visits with Michael Baute in Berlin between 2009 and 2012, or Volker Pantenburg’s visit to Chicago in 2012. One or both of them shared digital copies of a French television program he produced in which he would play a short scene from a film in its entirety, then spend several minutes dissecting the scene with live commentary, and then play the scene in its entirety again.

That last step, to play the scene in its entirety once more, after the analysis has been performed, I’ve always found poignant. Like putting something back together again after having dissasembled it to understand all of its inner workings. It’s like a magician’s act, where you see the thing, then see it turned inside out, and then see it once more as you did the first time, except now you see it all differently.

There’s also a certain respect for the integrity of the finished work, to let it have the last word, even while bearing a host of fresh insights in mind while watching it one more time. Today’s videographic work (and the culture in which it operates) either has no consideration or no patience for this last step of “reboxing” the work, after the “unboxing” has been performed. There may also be legal considerations involved – to let a clip run without critical commentary violates fair use guidelines as they are commonly understood. To count as fair use, a videographic work must somehow “transform” the work into something new and distinctly detached from the original – in other words, it must abandon the original work like a grown child leaving their parents.

But then one looks at such respectful work as Bergala’s, which insists on returning to the work, synthesizing its with one’s own new insights in an act of spectatorial and critical recombination, forming a new dynamic that encompasses both the work and the viewer. Creating a productive friction with something means to remain engaged with it, to try to keep things together under an ethos of respect. If this doesn’t fit current fair use guidelines, then one must ask, what can we really consider to be fair to the film?

For more thoughts on the importance of process and artistry in video essays, read this piece by Conor Bateman, from his series of articles on video essays.