If the blog has been relatively quiet for the past several days, it’s due to recent activities involving travel (talks at the École normale superieure in Paris and the University of California at Davis) and groundwork for future engagements beyond the Farocki Residency. It’s sad to think that this special three-month residency period is now in its final week. I cherish what I was able to do in this window of time that was unlike anything else I’ve experienced, even if it amounted to just a portion of what I hoped to do.

Among the things that occupy me at present are answering interview requests, one of which will be published on the website of the Institute for Contemporary Art in London in advance of my presentation there on March 30, as part of the Essay Film Festival. For efficacy’s sake, I referenced past interviews to see if I’d already answered some of the questions. In doing so I retrieved answers to interview questions emailed to me by Tilman Baumgärtel for an article published in Die Tageszeitung on April 15, 2015. As it turns out, little of the interview was quoted for the article, so I post it here as the answers still speak for me, and reviewing them lets me reflect on how to carry forward with my work (one of the major objectives I’ve had for this residency).

It also happens that Tilman Baumgärtel is curating a special program for the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen on “Social media before the internet.” I will be covering this program for Sight & Sound using its social media platforms, as a way to stage a dialogue between social medias past and present. It’s quite possible that I may be returning the favor of interviewing my past interviewer as part of this coverage. For now, here is our email conversation from two years before:

Question and Answer with Tilman Baumgärtel, conducted via email, March 4 2015

- Commenting on films by making films seems to be a most obvious idea, yet there are not many people doing such video essays on a regular basis. Most film criticism is still written. Why do you think that is? And how did you get on that path of making this kind of videoessay/review? (If you have a CV that is more extensive than what is on the www.alsolikelife.com sit, please send it along. I am particularly curious about your academic background, or rather, if these video essays came out of anything that you studied in university. And if the Transformers-film was your final project at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.)

In the early 2000s I started as a young filmmaker without any formal training from university or film school; I just taught myself by reading books, searching the internet and practicing. Over time I started writing criticism as a way to improve my films. But my criticism is mainly interested in understanding how movies work more than in writing a review. Eventually I combined filmmaking and criticism to make video essays. I made my first video essay in 2007 on my blog. By now I have made over 250 video essays for several websites. For the most part, the original motivation remains the same: using filmmaking and criticism together as a way to learn, discover and teach myself something new about cinema.

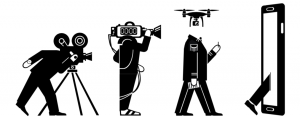

Most film criticism is still written because writing remains a useful traditional mode of communication. But the digital media revolution has created the YouTube/iPhone era of personal media making, and a new generation is already comfortable with using images to express themselves. Video essays are now being used to teach cinema in schools, and students are learning how to make them as a way to communicate their ideas.

Germany has a great pioneer in this field named Michael Baute. He is a film critic who gives video essay workshops in universities all over Germany. In fact, I was inspired by him to do the same in the U.S., but teaching at U.S. universities requires a Masters Degree. That is why I went back to school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. But fortunately this school has an amazing program that inspires great experimentation and raised my work to another level. I finished Transformers: the Premake in just my first year at the school. I am already working on new projects for the second year.

- You often use clips from films that were just released. Where do you get those clips? And has there been any problems in regards to copyright yet?

I’ve had recurring problems with copyright; in 2009 my YouTube account was shut down due to claims of copyright violation. Fortunately, several film critics complained about this, and it led to more publicity and awareness of video essays as a legitimate use of found footage. These days I seem to be able to work with less interference, partly because the movie studios have realized that this content can be used to promote their films. In fact, I am now more suspicious of video essays that purely work to celebrate movies, because it becomes another form of advertising. I think video essays should keep pushing the boundaries of how we can talk about movies freely, critically and thoughtfully.

- Are there any short-comings to the video essays? Are there ever situations where you think: I wish I could write an essay?

I still enjoy writing essays; I recently published a 3000 word article on Transformers in the academic media journal Incite. Of course writing can express certain ideas better than video. One problem with video essays is that they can be used to conceal poor thinking. I think there are quite a few video essays that use video to dazzle the viewer with cool editing and images, but actually don’t have very strong arguments. They create a sensation of being profound without actually being so – just like a Christopher Nolan movie!

- Doing video essays also means that you have to be an editor, narrator, credit designer etc. One could criticize that as a new way of forcing the cultural worker to be more flexible (Walter Benjamin never set his own writings in typeface…) Or do you enjoy the creative freedom that this brings?

Yes, I recognize there are two sides to this. There have been film critics who look at video essays with concern, because of the increased amount of work and skills involved, and how it may lessen the value of having a single skill. Even for myself, in addition to all my work to make these videos, I often have to promote them myself. (Benjamin never had to be his own advertiser on Twitter or Facebook). This is the paradox of our age: we have more tools to do more things on our own, but the sense of value for all this work is diminishing, or at least it is changing radically.

We should also consider how much of this work is blending with what used to be considered leisure activity. The person happily posting videos on YouTube or Facebook is unwittingly performing unpaid labor that creates value for those websites, and it also competes with the media content made by professionals. The blending of work and play is the new normal of the digital media age. And it is creating a new economy of personal values, with such concepts as “social capital” and “affective labor” – followers, likes and retweets – replacing money as the reward for our efforts.

- How is the compensation for these video essays? This is less about what the sites actually pay you for your pieces, but if you feel that the compensation is in a fair relation to what you create. For written texts there are certain fees, for video documentary there are other fees, but for creating video essays out of existing films, there might not be such an agreed-upon fee…

Maybe number 4 is my way to answer this question; at least I think what I wrote above is more crucial to the situation than the issue of fees. At least know that the issue of the fee – not just for video essays, but really all media content – is unstable precisely because of the conditions I described above.

- Any plans for another production along the lines of the “Premake”?

I’m interested in using the desktop documentary approach again in the future, if I find the right subject to match it. I don’t want to just apply it like a cosmetic surface without a real purpose. More crucial for me are the issues of the social and economic value of image-making itself. This is a key theme of Transformers: The Premake and it’s also in my new projects. Last fall I discovered that half of the film and video art in Chicago’s most famous museum are on YouTube without any legal permission, and so I created a YouTube playlist of the videos and presented it to the museum. I am now working on a project involving the filming of banks, which are very controlled, restrictive spaces. This is interesting to me because these days we seem to have unprecedented control and freedom to make images. I want to see how those freedoms are put to the test.