Continuing the year-by-year account of my past decade making video essays (see past entries on 2007, 2008, 2009-10), I now look at 2011, my first – and only – year in which I was fully employed as a video essayist. In 2011 I produced 12 video essays, which can be found here.

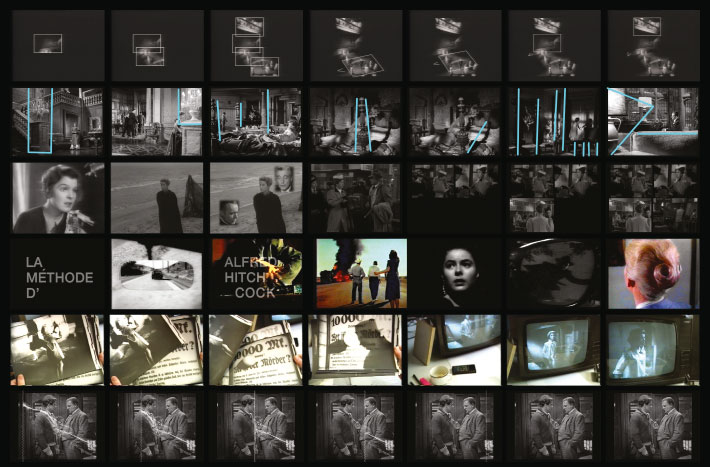

In my previous entry I discussed how YouTube’s sudden shutdown of my account triggered publicity and expressions of support for my work. I neglected to mention some especially important supporters at the time: the organizers of a project called Kunst der Vermittlung (The Art of Mediation), a website and screening series drawing attention to “Filmvermittelnden Films,” or works of cinema that focus on the cinema itself.

As described in the project website (via Google Translate):

A Filmvermittelnden Film can be an artistic video work that collects typical settings from a director’s films in a montage; Or a documentary about the motifs of a genre; Or a “cinematographic”, didactic film about the schooling of children at school. The genre includes many formats: experimental, analytical, didactic, essayistic forms for cinema, television, museum, school.”

A month after the YouTube shutdown, I met one of the organizers of Kunst der Vermittlung, Michael Baute, who told me about the project and invited me to Berlin to present my work as part of the series. My participation would represent Filmvermittelnden Film as it existed on the internet, one of the project’s 18 focus areas of key topics as well as key figures. Through taking part in the project and meeting with its organizers, such as Volker Pantenburg, Stefanie Schlüter and Stefan Pethke, I first became acquainted with the analytic film and media works of Alain Bergala, Jean Douchet and Harun Farocki.

This experience had no small effect on me. It was the first time that anyone had taken my work seriously, not just under a convenient label of “internet film criticism” or “YouTube video,” but something harder to categorize, or rather, something worthy of a categorization that resists convenience. This, more than just being “films about films,” was what distinguished the works assembled by the Kunst der Vermittlung project: that they all reflected inspired acts of engaging other works of cinema, and through this inspired viewing, they could devise inspired new forms of creating cinema. It was revelatory to discover so many of these works spanning across the past five decades, and humbling to think that my work might connect to this legacy, one still in the process of becoming fully recognized.

At the same time that I was exploring the potential of video essays to be creative and artistically innovative (with the works featured in Kunst der Vermittlung serving as inspiring examples), I was also connecting to a legacy found in U.S. mainstream media. Film critic Roger Ebert had a great influence on my formative years, as he had for many cinephiles of my generation, both through his extensive collection of reviews as a regular newspaper critic, but also as a nationally broadcast critic on his TV show with fellow critic Gene Siskel. Much has been said and written about Ebert’s importance – there’s even a feature documentary that was made following his death in 2013.

As an illustration of his appeal, here’s a clip of his review of Oliver Stone’s JFK, which he considered the best film of 25 years ago. It was a controversial choice but Ebert’s passion is infectious, partly because he is not just advocating for the film, but for a certain kind of filmmaking – bold, challenging difficult – that’s all but extinct in mainstream Hollywood cinema and is even stunning to think was possible 25 years ago. It is also apparent how valuable it was to have a mainstream television show for him to voice his advocacy for this work – and in doing so, advocate for intelligence and curiosity in a mainstream film culture at large.

It was no easy task, and the show was often criticized for “dumbing down” film criticism by reducing it to soundbites, as well as their patented “thumbs up / thumbs down” rating system. But the challenge of bringing worthwhile discussion and appreciation of cinema into an American commercial broadcast is no easy task, and looking at the state of American television today and what place any sort of intelligent culture has in it, I can be forgiven for considering this a positive example of what was once possible.

Needless to say, I often fantasized about what it could be like to be on this show. And through a series of unexpected developments, this fantasy become real in 2011. Ebert had learned about my video essay work through mutual friends, and eventually invited me to contribute a video segment. Using my video essay skills and combining them with on camera reporting, I submitted two reports, one on Korean cinema and this report on Chinese cinema. It was the first and only time a report on Chinese cinema had been featured in the show’s 35 year history. This also became an opportunity to experience firsthand what it is like to take a long, complex topic and distill it into a few minutes worth of soundbites. In fact, the video below was shortened by two minutes for its eventual broadcast release.

Sadly, this segment would air in what would be the final season of Ebert’s weekly film review program, due to Ebert’s mounting health problems and a declining viewership. But I’m glad for the part I could play in Ebert’s final season, for the tremendous part he played in developing my own passion for film.

One may suppose that these two deeply influential experiences, Kunst der Vermittlung and Roger Ebert, represent twin poles of film criticism practice: artistic the commercial, marginal and mainstream. But then one remembers that the Kunst der Vermittlung project encompassed works that were produced for European television in the 60s, 70s and 80s, such as those by Douchet, Bergala and Farocki. As with Ebert in the U.S., such television programs are unthinkable now in Europe. As with many institutions that dominated the 20th century, broadcast television is in decline (what gets celebrated as “the golden era of television” these days is really streaming media), and cinema, at least as it was appreciated in Ebert’s time, may be following its wake. The question of how to keep a certain kind of cinema alive for a generation more connected to desktop and mobile screens than silver screens became a crucial one for the next role I would take on in 2011.