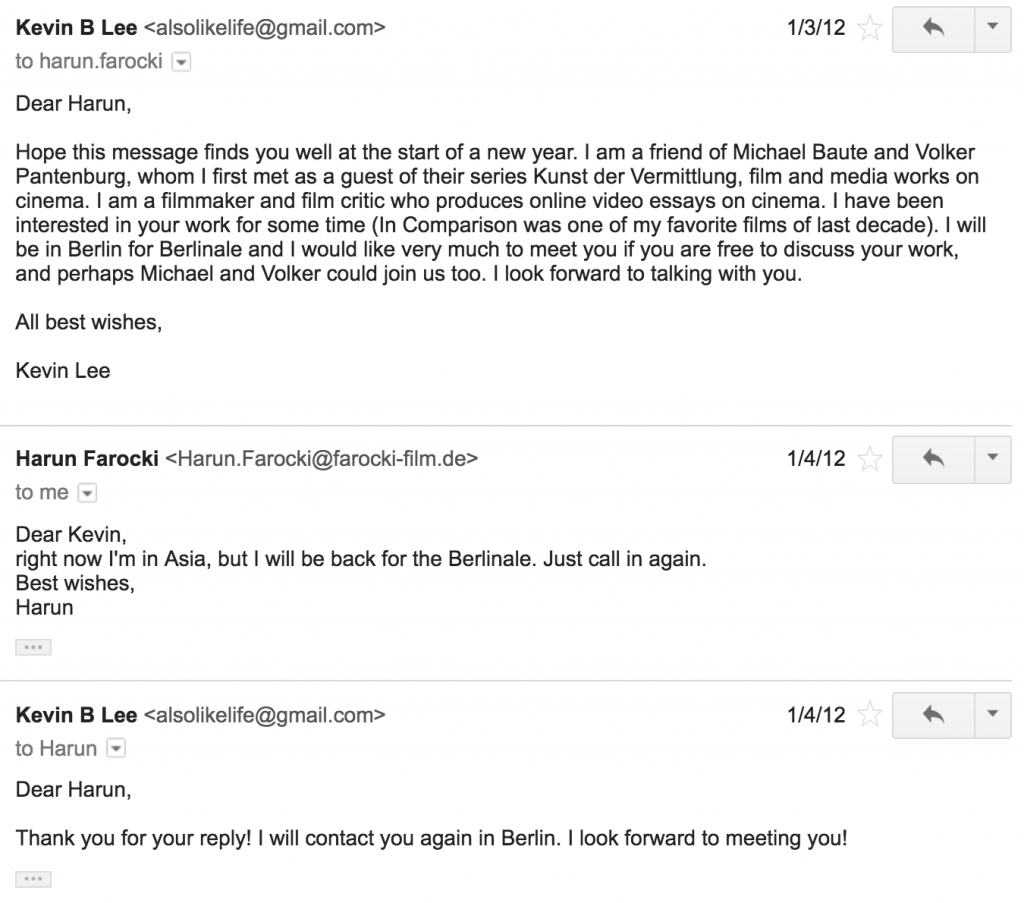

Film critic Andreas Busche recently asked me if I had ever met Harun Farocki. I met him exactly once, almost exactly five years ago, during the 2012 Berlinale. It was at the premiere party for the film Barbara directed by German director and Farocki collaborator Christian Petzold. It was a festive but distracting environment full of people, so I don’t remember much from the exchange. (I had a more significant conversation with his partner Antje Ehmann, who said some nice things about “The Spielberg Face,” which I had just recently published.) But yes, I can say that I met Harun Farocki, though it happened haphazardly and despite a more deliberate (albeit equally awkward) initial attempt to do so…

I think it was Michael who encouraged me to write to Farocki. I’m startled by my addressing Farocki by his first name despite never having met him. (I seem to be more respectful when not addressing him directly, as evidenced by the discussion that takes place at the 2:45 mark in this video.) As it happens, we never did set a proper appointment to meet. I followed up a few weeks later but didn’t hear back. When I brought it up with Michael I think he told me that Harun is very busy and would perhaps be more inclined to meet if I had a specific agenda or objective in mind. I really had none, other than to spend time talking with him.

Now I find myself in a situation where I am very protective of my time here at the Harun Farocki residency, thinking what is the best use of my time, and what agendas or objectives are most worth setting. I am presently reading a 2001 collection of his writings titled Nachdruck/Imprint. In many of his texts there is an extraordinary sensitivity to matters of labor, time and value in his reflections upon art and life. Take for instance this paragraph in “What an Editing Room Is:”

Film script and shooting schedule are ideas and money; shooting a film is work and spending of money. The work at the editing table is something in-between.

In his introduction to this collection, Volker Pantenburg quotes Farocki’s description of his work as a “composite system… where every waste product flows back into the production process and hardly energy is lost:”

I finance the basic research with a radio show; books studied during the research period are dealt with in shows on books, and some of what I observe while doing this work appears in television shows.”

This seems like the very model of creative efficiency, but it is also one of utmost necessity for survival as an artist. As Volker (I feel familiar enough to refer to him on a first name basis) writes: “This combination of various branches of work was not voluntary, but a kind of self-defense, in order to stay afloat financially.”

But one should not mistake Farocki’s preoccupation with work as a prioritization of economy over creativity, much less humanity. Quite the contrary, his extensive writing and filming on the relationship between labor and culture reflects an extraordinary sensitivity towards the impositions of economic materialism upon the human mind and spirit. However, in a rather ingenious reversal, materialism becomes the raw material upon which his critical mind and creative spirit exert themselves.

These are things that I am thinking about as well, more than I ever have. Perhaps this is the conversation I was meant to have with Farocki, to be acquainted with him and his world well enough to earn the right to call him “Harun.”

Just finished reading all your posts so far. Immensely enjoying reading/watching what you posted and getting a glimpse of your residency and the changes you are dealing with from a distance. I love (and glad) that you are sharing this on a blog (I too have been questioning the value of ‘blogging’ and frustrated with everyone’s short attention span, but for now, I’m holding on to it). I look forward to reading more, learning and discovering.