With the previous entry on 2014, I commented on the extent to which video essays had by that point yielded a vast and growing range of techniques to explore film and media. At the same time, I was becoming more interested in exploring the space outside the screen:

That was from a presentation I gave in graduate school in the fall of 2014. (The full presentation can be viewed here.) This was near the start of a period when, following the release of Transformers: The Premake, I began to receive invitations to give talks at film festivals, schools and other venues. Here’s one on video essays from the Boston Independent Film Festival in April 2015, and one on desktop documentary from March 17, 2015 at University of Sussex.

But the most performative and experimental presentation I gave was at the 2015 Society of Cinema and Media Studies annual meeting.

I served as a respondent on a panel on Harun Farocki’s legacy, with presentations by Volker Pantenburg, Ute Holl and Trond Lundemo, all established Farocki scholars. Being a far less qualified and erudite participant than my fellow panelists, I adopted the role of being a student interested in learning more about Farocki, realized through my interactions with my fellow panelists and other Farocki scholars attending the conference, as well as my independent online research as a curious student would typically perform. I combined these two modes of investigation into this presentation, most notably in the anecdote that begins at 1:30.

Film scholar Rembert Heuser, who attended this talk, would later comment that this mode of desktop criticism distinguishes itself from other forms of video essays in that it “sticks to the ethics of criticism for bringing the very conditions of its analysis to the foreground. Characteristic to this approach is a multiplicity of screens.”

I’m certainly not the first to treat the screen as an object of scrutiny. Shortly after this conference, I produced this video essay on the films and video essays by Mark Rappaport, whom I identified as a key forebear of contemporary online video essay production, as well as a roster of other legends, listed at 0:25 in this video:

What distinguishes Rappaport from just about any video essayist I know is his unique approach to constructing a dynamic relationship between himself and his subject. His use of live actors and scripted narration to impersonate his subjects are significantly more invasive than the standard practice of re-editing found footage. They create a third dimension between that of the filmmaker and the screen subject, while allowing the two to commingle in a space of speculation that is both critical and creative. (His newest video essay cleverly locates this commingling of subject and screen within many instances in movie history)

By comparison, the screen interpolations performed by myself and other online video essayists are fairly tame. The following two videos probably exemplify my best efforts of 2016 to engage critically with the screen. The first is a fairly straightforward side-by-side comparison of comparable sequences from the two versions of the film Insomnia, the original Norwegian production and the Christopher Nolan-directed Hollywood remake.

And then there’s this video, which was originally produced in 2013 but was shelved when its original commissioner rejected it for its violent content and/or seemingly unfavorable depiction of Quentin Tarantino’s films. If anything it might reflect a growing frustration on my part of the limitations of screen reality and a desire to reinvest screen fictions with a dose of the real, especially depictions of violent death serving entertainment purposes.

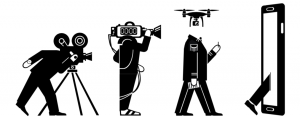

Increasingly, I feel more constrained by the space of the cinematic screen and desire to break into some as-yet-untapped dimension of the real. By the same token, I wonder how the “cinematic” (however we understand it) spills into the real world and informs real world operations. Most of all, I think upon the extent to which these investigations require the creation of new images, and what those images might look like.