In 2014 I produced 52 video essays (48 of which were weekly entries for Fandor) while in my first full year of graduate studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. This would seem like an overwhelming workload, but it was really a virtuous cycle where the fresh encounters of ideas at school inspired new approaches to my video essay work. In turn, the video essays helped subsidize the costs of my education.

This period yielded probably the best edition of the “Who Should Win the Oscars” videos that I produced annually from 2012-2016. I used this series to apply different videographic analysis techniques to understand the Academy Award nominees. Most notably I used cinemetrics, the statistical-based measurement of different aspects of cinema, to find a different way to understand how performances work on viewers. I was specifically interested in the issue of screen time: does how much time an actor spends on screen affect our response?

What I didn’t expect to discover was that the Best Lead Actor nominees had nearly twice as much screen time as the Best Lead Actress nominees, suggesting an inequality between the sexes playing out on the screen itself. I reported my findings to the New York Times, the first appearance of cinemetrics research in a major newspaper.

But there were other, more nuanced observations to be made in applying cinemetric research to performance studies.

In this video essay on the Best Lead Actress nominees, my analysis of Sandra Bullock’s performance in Gravity breaks down her appearance in the film into the amount of time we see her face and body, and compares it to the amount of time that we hear her voice and breathing. Performing this analysis led me to see (or rather, hear) to what extent Bullock’s sounds carry her performance in the film, and conclude that this was a “new kind of performance that serves a new purpose for the viewer. It grounds them in a bodily experience even as they drift among images of outer space.” Looking at this video again, I also see to what extent the performance is related to the aesthetics of embodiment in first person shooter-type video games, pointing at a transmedia dimension to this film that warrants further exploration.

But these possibilities to explore cinema beyond the cinema were manifesting elsewhere, like this video essay on that year’s Best Picture nominee Her. I staged a dialogue with my smart phone as a parallel nod to the film’s exploration of humans’ conversational relationship to technology.

At the same time that I was making these videos, I was also working on my main graduate school project. I’ve written extensively on this work elsewhere at The New York Times and Slate, and most extensively in a chapter for the recently released book The State of Post-Cinema: Tracing the Moving Image in the Age of Digital Dissemination. There’s also a video of a talk I gave on the making of the film at the University of Sussex, recorded by Catherine Grant.

I’d like to think that this video does a lot of speaking on its own behalf… but at the same time, I don’t think it would have had the impact it would have had I not coordinated a media blitz around its release thanks to coverage lent by many colleagues in the film critic community. Doing this was crucial, as I had a relatively narrow window to take advantage of all the pre-release hype surrounding the subject of this video essay and direct it towards my own work. For me it cemented an understanding (articulated in this video) that a film isn’t just a film, but a complex network of activities in and around it that combine to form its “material”, which may amount to nothing more than the amalgamation of the immaterial: our collective hopes, dreams and energies.

I should also mention one of my own hopes and dreams in making this video, related to the matter of voice. With this video I undeniably discovered a new voice for myself, that is to say, a new way to tell a story without even using my voice. This was a challenge I’d set before myself since my early days of making video essays back in 2007-2009. Daniel Kasman, editor of the famed Mubi Notebook, had written praise on behalf of a video essay by Gina Telaroli for how evocatively it conjured ideas and impressions through an associational montage of images while not resorting to voiceover at all, which he felt was technique used all too often in video essays at the time. I didn’t know if he had my work in mind, but I became painfully aware of the extent to which I resorted to voiceover, and since then had yearned to find a way to free myself of that technique. This desire redoubled upon hearing Farocki’s quote mentioned in my 2012 entry, the desire to see “images commenting on images.”

These dilemmas aren’t unique to video essays, and can be detected in the works of filmmakers of past generations. I discovered this in working on a video essay for Sight & Sound on the works of Robert Gardner, following his passing in 2014.

The issue of voice also appears in this video essay made at the end of the year, the first video essay about video essays. By this point there were so many practitioners and contexts for understanding the video essay – fan vs. scholar, amateur vs. professional, instructional vs. exploratory, commercial vs. non-commercial – that I had to take a moment to make sense of it all for myself. I resorted to a voiceover narration – or hyper-narration, if you will – while remarking critically on how voices and images are used in these works.

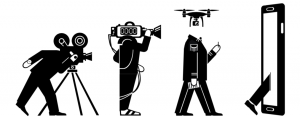

This video makes clear just how many approaches and tools had been developed to work with moving images and media to create video essays. But for all of these options, there were still others not accounted for, and not confined entirely to the space of pre-existing footage, or even the space of the screen.